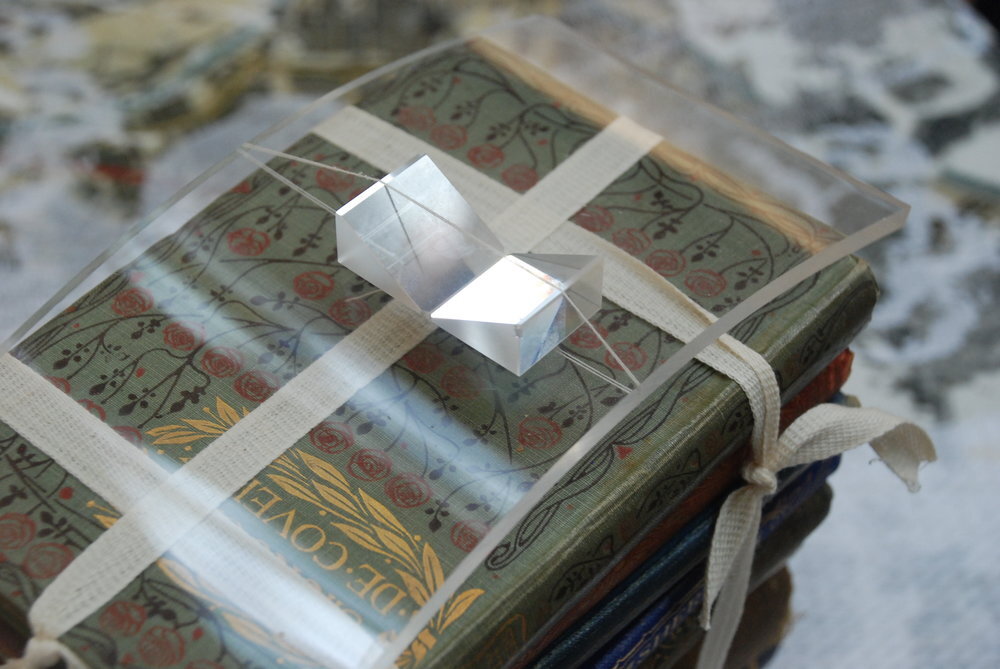

Maria Nepomuceno, The Force, 2011. Ropes, beads, fibreglass, resin and ceramic. Courtesy of the artist and Victoria Miro. Photography: Andrew Brooks. © The Portico Library.

Refloresta! Maria Nepomuceno

The centuries-old books that populate the Portico Library’s Regency-period bookshelves are alive. Some of them have been sleeping for a long time, but they are alive. And now they have company.

World-renowned Brazilian artist Maria Nepomuceno’s expansive sculptures sprawl and stretch around the Library like giant living organisms in search of something. A new source of power? They grow through osmosis, drawing strength from the ultimate force—knowledge—and through exchange of energy and affection with the people that come to see them. There’s nourishment in the 25,000 Georgian and Victorian books encircling us in this spectacular room: visionary breakthroughs in maths, medicine, and human rights; founding principles of modern science. There are toxins too: stories of colonial expansion written by the powerful, for the powerful, as if they were histories; descriptions of fruitful new species of plants and animals to be harvested and propagated from the rainforests to the plantations; and pseudo-scientific rationales for the extraction and exploitation of peoples and their lands, forests and oceans, in the name of progress and civilisation.

Here in Manchester today, in the room at the heart of the Industrial Revolution’s ‘first modern city’, a very different kind of colonisation is taking place. Technicolour creations in ropes and pearls, built with love to disrupt and delight, are invading and inhabiting the space. And an invitation has gone out to the city’s people to come and bring it all to life. The Library’s visitors during this exhibition are welcome to pose within the central artwork with friends, family and fellow visitors and capture their interactions in drawings that will in turn be added to the evolving display.

Maria’s pieces, combining fluid forms with traditional rope-weaving and straw-braiding techniques, are shown here alongside natural history books and archive materials from the Portico’s collection illustrating Manchester’s international connections during the city’s formative years. With spiral patterns evoking biological and spiritual themes, her vividly coloured artworks have brought the vibrancy of the natural world into the Library’s tranquil interior.

Refloresta!

As we emerge from a devastating pandemic, Maria Nepomuceno asks us to remember the emergency of our time. Her exhibition’s title, Refloresta!, means ‘reforest’ in Brazilian Portuguese. It evokes the environment in which the artworks were conceived—Maria’s studio among the towering fruit trees of Rio de Janeiro—and her wish for the world to come together to reverse the deforestation still ravaging the globe. In a room and a city that bear the scars of industry—books blackened with Victorian soot and civic spaces devoid of wildlife—Nepomuceno’s organically shaped sculptures and the Library’s natural history books that accompany them remind us of what we could create: green, biologically diverse cities, where multicolour life and multicolour ideas thrive.

The central artwork, The Force (2011), has previously been shown in exterior settings exposed to the elements, and here envelops the historic bookshelves and balustrades under the natural light of the Library’s great glass dome. Encroaching into the central public space, it interrupts the Library’s activities and demands our attention, calling us to slow down, look around, and re-engage with our world. The ceramic vessel-like elements of its companion piece, Untitled (2011), resemble laboratory equipment, overflowing with life. The complete form of the exhibition will depend on its visitors, their poses and interactions shaping its content and composition as it unfolds over the months.

The Library today

Alongside those who profited from colonialism and industrialisation, the Portico’s early membership included pioneering naturalists and scientists: founders of the now long-gone Manchester Botanic Garden; anti-slavery campaigning doctors and anthropologists; and leaders in atomic theory and medical ethics. Their legacy helps to shape the Library today—its focus on cooperation, curiosity and speculative research, and its aim to nurture a lifelong love of learning in all people. This exhibition coincides with the launch of an ambitious development process for the Library, revitalising its stunning building for the 21st century as an innovative heritage, arts and learning centre with and for all of Manchester’s communities in the heart of the city. Refloresta! reflects the Library’s long international history of global connections (today’s tourists follow in the footsteps of 19th-century guests from St Petersburg, Havana and Buenos Aires) and invites us into the worlds between the book covers, and the stories between the lines.

The books

Today, the Portico Library welcomes people from all walks of life to enjoy its historic spaces and collection for free. When it was established 215 years ago during the Regency period, it served only its 400 shareholding proprietors and their guests. These writers, politicians, mill owners, scientists, doctors and clergymen—the new middle class of the fast-expanding industrial city—collected books that suited their interests: texts on technological innovations, accounts of growing empires, political tracts, and volumes on ‘natural philosophy’ (biology and physics). Illustrations of flora and fauna adorn many of these books’ covers, indicating their readers’ fascination with the natural world and their curiosity about the newly encountered lands beyond their borders. The books themselves now form a unique resource for researchers, members, and readers who draw upon the insights and evidence they contain as to where so many of today’s debates and developments were born.

Contemporary textiles and feminism: foreword, 2017

Curated by Sarah-Joy Ford with essays and conversations from Lubaina Himid, Christine Checinska, Janis Jefferies, Alexandra M. Kokoli, Julia Skelly, Pennina Barnett and more...

Sold out

Many-Splendoured Thing.

Gê Orthof and Raphael Fonseca at The Portico Library

Gê Orthof and Raphael Fonseca’s remarkable exhibition Many-Splendoured Thing is unique for The Portico Library. At a time when Brazil’s political and social situation is dominating the news, Prêmio Marcantonio Vilaça Award winners Gê and Raphael have travelled from Rio and Brasília to undertake a residency here at the library, interrogating the books and history of our spectacular collection, and creating a playful, poetic response that brings the literature to life.

Enchanted by books and their power to unlock new worlds of potential, Gê has built a space for visions to take form and journeys to begin. His miniature dioramas invite us to join and get to know them, feeling ourselves fellow characters in these strange, intriguing stories, all bound together between the pages of his ‘street library’. With humble materials and dreams of magic, Gê has temporarily transformed the entire gallery space into one flowing, immersive installation, whose cardboard walls remind us of both the shelters of rough-sleepers and refugees, and the materials from which our books are made. Finding ourselves standing down among the pages, we begin to imagine the scenarios and dialogues occurring, and our own evolving roles.

In So Many Words: Roget’s Thesaurus and the power of language

Manchester rarely celebrates its connection to Peter Mark Roget, perhaps the most influential linguist of the 19th century. Born in 1779 into a family of Huguenot refugeees, he studied physiology in Edinburgh before moving to Manchester, where he served as the Portico Library’s first Secretary from 1806. His achievements are remarkable and diverse–from groundbreaking work in medicine and metrology (the study of measurement) to serving at the Royal Society, his influence can be found in the development of film, computing, health, and of course, lexicography. Alongside original minute books hand-written in Roget’s own script, the Portico Library preserves documents of his invention of the slide rule and study of the persistence of vision, plus papers on number generation and cranioscopy (an argument against the pseudoscience of phrenology). After a turbulent early life, during which he witnessed his beloved uncle’s suicide, Roget experienced recurring depression, and found therapeutic benefit in the absorbing, decades-long work of compiling his Thesaurus. It is believed he took inspiration from the ancient Indian writer Amarasimha’s Sanskrit word list, the Namalinganushasanam, and his table of classification is influenced by Leibniz’s philosophy of symbols.

Made in Translation

The Portico Library’s 25,000 books, archives and illustrations span more than 450 years and include many rare and significant volumes, from Milton, Blake and Gaskell, to Darwin and Captain Cook. The breadth and influence of these titles have provided the starting points for Manchester Metropolitan University’s 2017 group residency and exhibition Made In Translation. Brought together by globally acclaimed textile artist Alice Kettle, this collective incorporates members of Manchester School of Art, with colleagues from the Writing School and the newly combined Faculty of Arts and Humanities. With the kind support of The Zochonis Charitable Trust, these artists, writers and researchers have continued the library’s tradition of uniting disciplines and combining ideas to bring the collection to the people of Manchester and beyond, with innovative responses in image, object and text.

For some of the artists and writers, particular volumes have yielded intriguing glimpses of an anterior world of ideas – one that brought forth our own, but that remains somehow distinct, somehow bygone. For others, short extracts have become as key-chains, unlocking new fields of investigation and offering alternative lenses through which to review contemporary concerns. The library itself has formed the subject for a number of the contributions, imagined simultaneously as a catalogue of catalogues, a hot air ballooning launch pad, a site of archaeological excavation and a storm-struck vessel, embarking on an intrepid voyage of discovery. While this variety of interpretations was hoped for and anticipated with Made in Translation’s initial vision, the depth and energy with which the participants have engaged has been a pleasure to encounter.

For each of the makers and designers, material is fundamental, but what could it mean without the language to conceive it? Likewise for the writers whose medium is text, what language is there but that of a material world? Among the diverse responses to these and other questions, one thing has shown itself time and time again: entering this singular space, exploring its bookshelves and opening up its centuries-old volumes never fails to inspire.